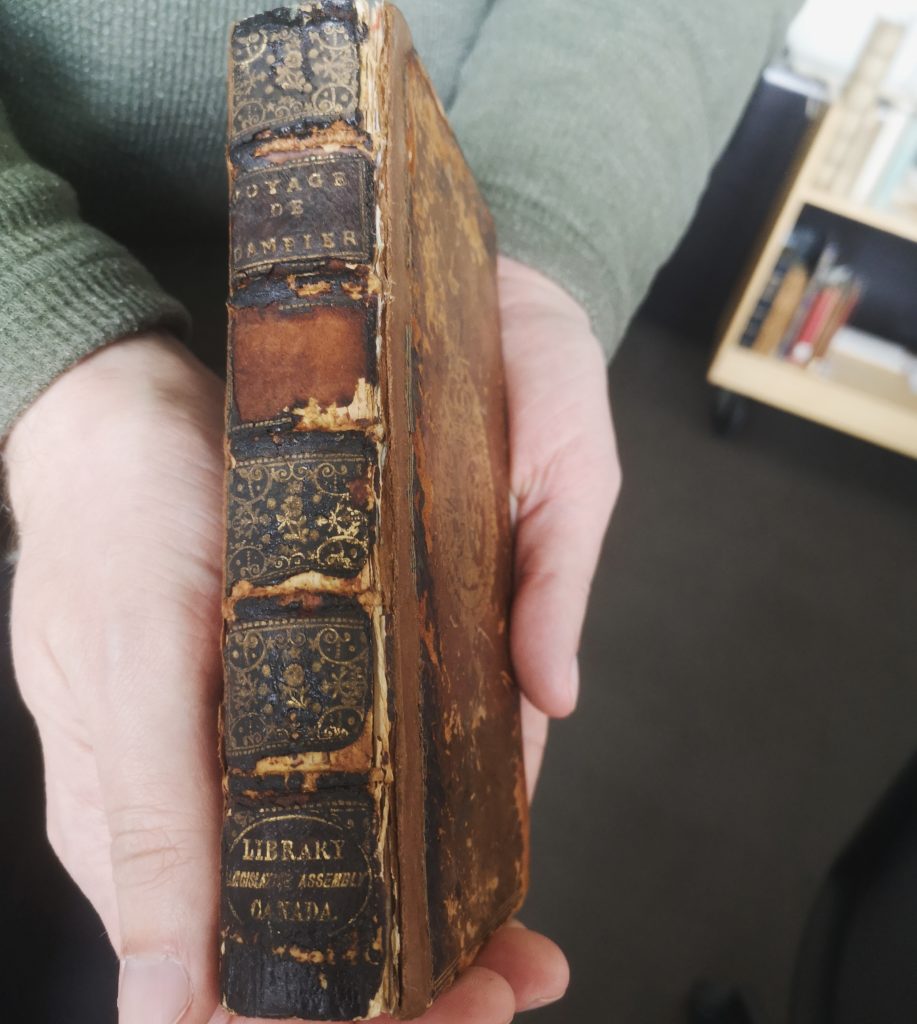

This March, the first-year Master’s of History students at Carleton University were invited to attend a workshop at Library and Archives Canada (LAC). Led by special collections librarian Meaghan Scanlon, the workshop featured a number of books from diverse acquisitions including (but not limited to) donations from the parliamentary library of Canada, gifts to Canada from the British government, and the private collections of Mackenzie King and other notable Canadian figures. The purpose of the collection is to preserve and provide access to rare works that are significant to Canadian history. Among the items that were shown were first editions of works by Lucy Maud Montgomery, a 1475 copy of Xenophon’s Cyropaedia formerly owned by Giorgio Antonio Vespucci (uncle of Amerigo Vespucci), William Dampier’s Nouveau voyage autour du monde, and Thomas Thomson’s A System of Chemistry of Inorganic Bodies donated to the LAC from the Molson family private collection (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1: Library and Archives Canada, A System of Chemistry of Inorganic Bodies [Fore edge showing untrimmed pages], Click on image to learn more (redirects to the LAC’s Flickr).

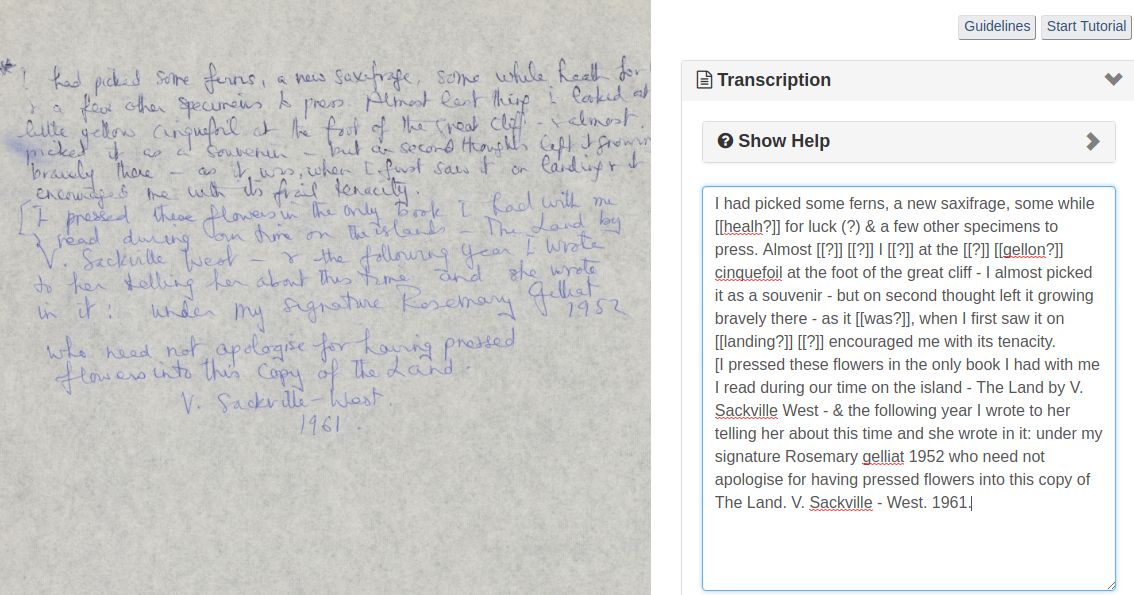

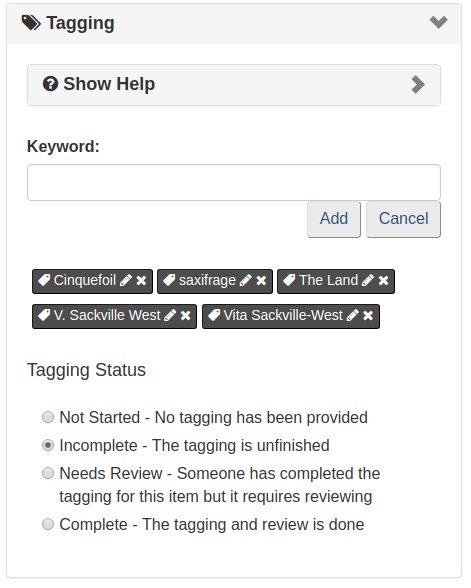

Scanlon gave the class a crash course in codicology, or the study of books as objects, by first showing us the book binding method employed in the creation of incunables (early printed books). To demonstrate how they were bound in quires, she folded a large piece of paper to create eight pages or leaves. For clarity, the University of Michigan library illustrates this idea in a lesson titled “What is a Codex?”. We later discussed how books reveal their history through the damages, repairs, and markings they accumulate over time. For example, the three volumes that made up William Dampier’s travel books (Fig. 2) had a fair amount of fire damage from the 1952 fire that broke out in Canada’s legislative library. Furthermore, there is evidence of post-fire repairs by conservators. Both of these events in this book’s “life” are now a unique aspect of this particular book’s history and transcend its original purpose and contents.

During the workshop, we discussed the contents of the books and their significance to Canadian history. The collection features books of reading lessons, a collection of short stories dated 1868-9 which were used to teach early Canadian children to read (Fig. 3). Items such as these are considered significant to Canadians for many reasons, including the history of education, the history of early Canadian printing, and more. Lucy Maud Montgomery’s novels are significant as an example of a female Canadian novelist. Provenance, including the origin and previous owners of a book, can be significant to Canadians as well: The copy of Xenophon’s Cyropaedia, as mentioned above, was previously owned by a relative of Amerigo Vespucci from whom the Americas were named. It was then housed and subsequently donated by the British government to the people of Canada in 1967 on the centennial of the confederation. (Fig. 4) These layers of meaning accrued through provenance transcend the contents of the book itself to have special importance to the people of Canada.

Fig. 3: Library and Archives Canada, Second Book of Reading Lessons, volumes dated 1868 and 1869 / Second Book of Reading Lessons, volumes datés de 1868 et 1869, Click on image to learn more (redirects to the LAC’s Flickr).

Fig. 4: Library and Archives Canada, Cyropaedia [British Government bookplate and first page of text] Cyropaedia [British Government bookplate and first page of text], Click on image to learn more (redirects to the LAC’s Flickr).

As a medievalist, what I found the most interesting throughout the workshop was the reoccurring theme of Canadians envoking the European Middle Ages. Through efforts such as the construction of Neo-Gothic architecture in Ottawa, the erection of statues depicting medieval characters and imagery, and in the rare books collected, it seems as though early Canadians were attempting to create an imagined Medieval past. Parliament Hill and the three buildings that compose it as well as the Notre-Dame Cathedral Basilica (1846) are examples of Neo-Gothic style. Pointed arches, stained-glass, sky-high pointed spires and exceptionally detailed decorations are some of the most iconic features of Gothic architecture that are shared with these buildings.

If you have ever walked by Parliament Hill, you may have noticed a medieval figure gallantly looking out over Wellington street. This statue is depicting none other than Sir Galahad, one of King Arthur’s knights of the round table (Fig. 3). But what is the stuff of Medieval legend doing outside Canada’s parliament building? Scanlon explains the piece was erected by William Mackenzie King in 1905 in honour of Henry Albert Harper, King’s close friend who died attempting to save a young girl who fell through the ice at the Governor General’s skating party in 1901. Despite the association between Sir Galahad and bravery, why did King make this choice? It is rumoured the choice may have come from Harper saying, “If I lose myself, I save myself” a line spoken by Sir Galahad in Tennyson’s The Holy Grail, moments before attempting the rescue. Whether or not this is true, Harper’s association with the knight runs deeper: he and King were immense fans of Tennyson’s Arthurian works and the two frequently discussed the tales. As the men were of British descent, it follows that these legends were part of their cultural awareness and the relationship between the Arthurian legends and nation building cannot be overlooked. Just as Geoffrey of Monmouth’s 1136 Histories of the Kings of Britain a pseudo-historical account of the foundation of Britain introduced the fabled King Arthur and his knights, it may have been King’s intention to evoke these characters once more in an effort to reaffirm the chivalry and bravery that he believed should characterise Canadians.

We find evidence of Medieval influence in the books that make up the special collections. For instance, the aforementioned Cyropaedia is reinforced with vellum, which was the most widely used writing surface in the Middle Ages. The book also features an illuminated initial letter in red and blue ink meant to emulate those found in medieval manuscripts (Fig. 4). Perhaps even more pointedly, the LAC has a single leaf from the Gutenberg Bible in its collection (Fig. 7). This piece is not a work of Canadiana, so why does it belong in this collection? Despite the obvious importance it holds as one of the earliest ‘mass’ printed books and the contributions the Gutenberg press made to print culture, I believe this item belongs in this collection for another reason. By housing this item in a Canadian institution we closely link European cultural heritage to our own. As a former colony of England and France, a large part of Canadian identity comes from the shared history we have with many Europeans. Although Canada strives and embraces multiculturalism today, our European ties still remain a big part of our history.

Fig. 7: Library and Archives Canada, A single leaf from an incomplete copy of the Gutenberg Bible / Feuillet d’un exemplaire incomplet de la Bible de Gutenberg, Click on image to learn more (redirects to the LAC’s Flickr).

The journey through time that Scanlon presented in this workshop was enlightening. By demonstrating the importance of the book as a physical object we were able to see that many different items belong in the Canadian collection because so much of our heritage comes from different places, times, and people —explaining the prevalence of Medieval visual culture in Canada. From travel journals to children textbooks, and the first mass-printed bible to a textbook on organic chemistry, the seemingly eclectic becomes unified in the Library and Archives of Canada’s special and rare books collection.

Bibliographical Information

Bartleby: Great Books Online, Nicholson & Lee, eds. The Oxford Book of English Mystical Verse. 1917. Alfred, Lord Tennyson ‘The Holy Grail’. Accessed April 16, 2019. https://www.bartleby.com/236/96.html

Library and Archives Canada Flickr, Rare Books / Livres rares Album, Accessed April 15, 2019. rhttps://flic.kr/s/aHsjVUoUBX

Notre-Dame Cathedral Ottawa, History. Accessed April 16, 2019. https://notredameottawa.com/history

Roy Mayer, Ottawa Citizen, “Ottawa’s Forgotten Hero”, December 6, 2007. Accessed April 15, 2019. https://www.pressreader.com/canada/ottawa-citizen/20071206/281814279522761

University of Michigan Library, “P46: What is a Codex?”, Accessed April 17, 2019, https://www.lib.umich.edu/reading/Paul/codex.html

![A System of Chemistry of Inorganic Bodies [Fore edge showing untrimmed pages] / A System of Chemistry of Inorganic Bodies [La gouttière montre que certaines pages n’ont pas été rognées]](https://live.staticflickr.com/7066/13538460103_9c90ac21b5_c.jpg)

![Cyropaedia [British Government bookplate and first page of text] / Cyropaedia [Première page de texte et ex libris du gouvernement britannique]](https://live.staticflickr.com/7063/13538473263_c58b80f3d4_c.jpg)